Hanging with the Saints

Building on our Faith at Home program, this year we'll be Hanging with the Saints!

The twelve saints below each play special roles in our parish, whether as patrons of individual classrooms, the parish, or our faith community as a whole. We'll be sending bi-monthly information packets to parishioners (including a short biography and prayer card) highlighting one saint a month. As we reflect on each holy man and woman, we invite you to pray for that saint's intercession, and join us for the month's special event! Our prayer is that you and your family will learn tons about these saints and that their intercession will draw you closer to the Lord and one another.

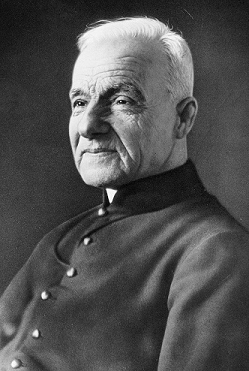

Saint André Bessette

Our January saint's feast day is celebrated on January 6, and our Catechesis of the Good Shepherd atrium (Classroom #2) is dedicated to this cheerful, humble saint!

Our special event this month is on Tuesday, January 11 from 7-8 p.m. in the Parish Center

- We'll be making clay figures and painting small wooden items for the atrium. No supplies or experience necessary - just bring yourself!

- As a doorkeeper, Saint André met many people and brought them closer to Christ. Through the CGS atrium (a word that refers to the entry of an ancient Roman home or temple), we hope to bring our preschoolers closer to Christ as well.

Who is Saint André Bessette?

When Alfred Bessette turned up at the door of the Congregation of the Holy Cross in Montreal, asking to enter the novitiate, the order’s superiors were deeply skeptical. The quiet young man before them could not read, could barely sign his own name, and chronic stomach pains prevented him from eating more than the simplest, smallest meals, leaving him unfit for physical labor. But in his hand was a note from his childhood pastor, Fr. André Provençal, who had simply written, “I am sending you a saint.”

After debate, the Congregation accepted Alfred, who took the name “André” in gratitude for the priest who had vouched for him. His first assignment was as doorkeeper of the college, prompting Br. André to later joke, “At the end of my novitiate, my superiors showed me the door, and I stayed there for forty years.” His duties were small and unimportant to most people’s eyes - wake the boys for their classes, greet visitors, deliver mail, run various errands – but Br. André did everything with a joyful spirit, never complaining of his illness or weariness.

Visitors often mentioned their own health concerns, however, and the monk gladly prayed with each of them. When he visited the sick, he always brought a medal of St. Joseph and blessed the patient with oil from the lamp burning before the statue of St. Joseph in the chapel. “Trust in St. Joseph and in the Lord wholeheartedly”, he would urge them, “and don’t worry.” Soon, word spread of miraculous healings. An epidemic broke out, but under Brother André’s care not a single student died, and the small daily gathering at his door became a traffic-stopping crowd.

Some were amazed, some suspicious. When questioned, Br. André insisted to everyone that St. Joseph had performed the miracles, not him – all he had done was pray. The insistence of others in praising him for the healings rather than God distressed the humble man greatly, at times to the point of tears.

With his superiors’ permission, Br. André began giving students haircuts for a nickel, patiently saving up until he could build a tiny shrine to St. Joseph nearby. Others began to donate toward improvements to the shrine, which soon meant the tiny enclosure had a roof, then heat. Within ten years, the little shrine had grown exponentially, with tens of thousands of letters pouring in weekly asking soft-spoken Br. André to pray for them. At his death in 1937 at the age of 91, millions of people traveled to file past his coffin and pay their respects.

Many of us can relate to the struggles Br. André dealt with daily. Despite his joyful nature and good humor, his stomach pains persisted through his life, a chronic illness that severely restricted his diet and physical strength. He had a quiet, introverted nature, but the role God called him to meant his days were filled with visitors seeking his time and presence. Instead of struggles, Br. André saw everything in his life as a gift given to an unworthy servant. “I am ignorant. If there were anyone more ignorant, the good God would choose him in my place,” he said. Because he saw himself as one of the “smallest brushes” in the Artist’s hand, humbly acknowledging his nothingness in comparison to God, God was able to work wonders through him. Is there anything in our own self-love that we cling to, unwilling to honestly admit that everything good in us was created and is sustained by God? What matters of pride can we take to prayer and offer to God, clearing the way for Him to create something beautiful with us?

Saint Josephine Bakhita

Our February saint's feast day is celebrated on February 8, and Room #3 (on the upper level of the Parish Office, closest to the door with the ramp) is dedicated to this holy woman who persevered in faith and hope through so many trials.

Josephine Bakhita

Our special event this month is on Tuesday, February 8 from 7-8 p.m. in the Parish Center

- In celebration of Black History month, we'll hear reflections on the first African woman to be canonized as a saint: Saint Josephine Bakhita.

- Our presenter will be Matuschka Lindo Briggs, a former reporter for NBC and ESPN affiliates who is also a wife, mother, devout Catholic, and a Saint Anselm parishioner.

Who is Saint Josephine Bakhita?

Josephine Margaret Bakhita grew up in a happy and relatively prosperous member of the Daju people in the Darfur region of Sudan. Then, sometime in February 1877, Josephine was kidnapped by Arab slave traders. Although she was just eight years old, she was forced to walk barefoot over 600 miles to a slave market in El Obeid. For the next twelve years she would be bought, sold, and given away over a dozen times. The trauma of her abduction caused her to forget her own name, so she took one given to her by the slavers: "Bakhita", Arabic for "lucky" or "fortunate".

As a slave, her experiences varied from fair treatment to cruel. One of her owners was a Turkish general whose wife ordered her to be scarred. A woman drew patterns on Bakhita’s skin with flour, cut into her flesh with a blade, and rubbed the wounds with salt to make the scars permanent. Eventually the Turkish general sold her to an Italian Vice Consul, who took her on a long and dangerous journey to Italy. Once there, she was given away to another family as a gift and she served them as a nanny.

When her new mistress decided to travel to Sudan without Josephine, she placed her in the custody of the Canossian Sisters in Venice. While there, Josephine came to learn about God. According to Josephine, she had always known about God, who created all things, but she did not know who He was. The sisters answered her questions, and she was deeply moved and discerned a call to follow Christ. When her mistress returned from Sudan, Josephine refused to leave. Her mistress spent three days trying to persuade her, but Josephine remained steadfast. The sisters intervened, and eventually an Italian court concluded that since slavery was illegal in Italy, Bakhita had actually been free since 1885.

With this newfound freedom, Josephine chose to remain with the Canossian Sisters. On January 9, 1890 she received all three sacraments of initiation: Baptism, Holy Communion, and Confirmation. She took the name Sr. Josephine Margaret Fortunata and entered the convent as a novice. After taking her final vows in 1896, Josephine spent the next 42 years of her life as a cook and doorkeeper at a convent in Schio, Vicenza. She also visited other convents, telling her story to other sisters and preparing them for work in Africa. She was known for her gentle voice and smile.

During World War II, the people of the village of Schio regarded her as their protector. And although bombs fell on their village, not one citizen died. In her later years, she began to suffer physical pain and was forced to use a wheelchair, but she always remained cheerful. If anyone asked her how she was, she would reply, "As the Master desires." On the evening of February 8, 1947, Josephine spoke her last words, "Our Lady, Our Lady!"

Saint Benedict

Our March saint's feast day is celebrated on March 21, one of two particular days the Benedictine order honors this holy man.

Our special event this month is on Tuesday, March 8 from 7-8 p.m. in the Parish Center

- Our presenter will be Abbot Gregory Mohrman, OSB, from Saint Louis Abbey, offering "Reflections on Saint Benedict" from his perspective as a Benedictine priest and life-long student of the Benedictine life.

Who is Saint Benedict?

Saint Benedict's times (c. 480-547) were as turbulent as our own, though for very different reasons. Benedict lived in sixth-century Italy when the great Roman Empire was disintegrating. He left his native Nursia to attend school in Rome, but became disgusted with the paganism he saw, and renounced the world to live in solitude in a cave at Subiaco, some thirty miles east of Rome.

In time, some monks asked him to be their abbot, but after experiencing how strictly Benedict lived, the recalcitrant monks sought to poison him. By a miracle, they failed, and Benedict left them, eventually founding twelve monasteries of twelve monks each.

Benedict intended his Rule to be "a little rule for beginners." It contains directions for all aspects of monastic life, from establishing the abbot as superior to the arrangement of psalms for prayers, from correction of faults to details of clothing and the amount of food and drink allotted to each. While some of these instructions have been modified by necessity in modern monasteries, the majority remain as the saint first wrote them.

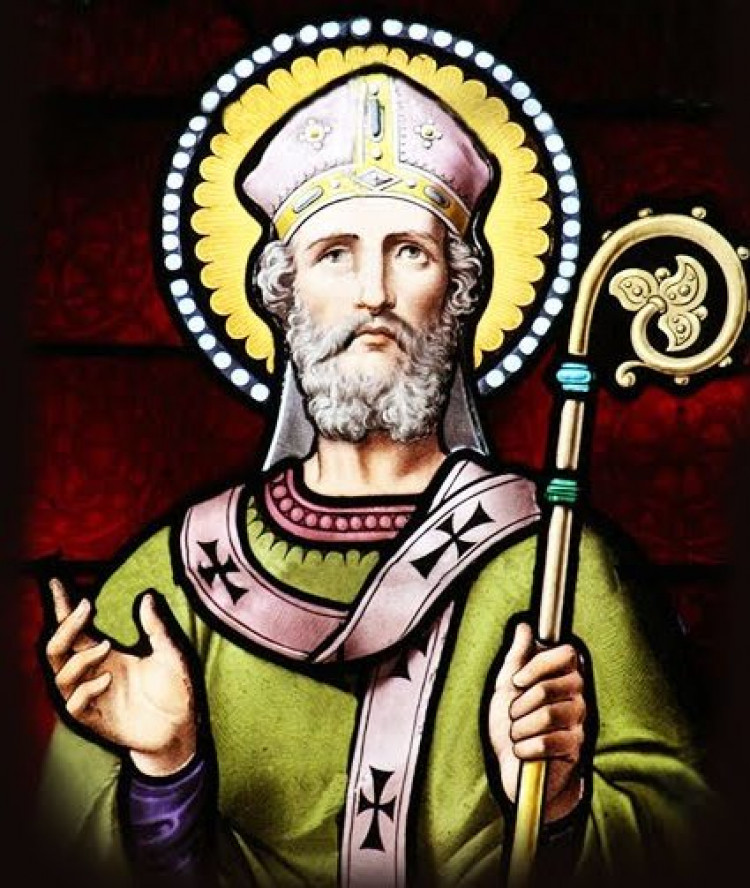

Saint Anselm of Canterbury

(1033-1109)

Saint Anselm’s motto is fides quaerens intellectum faith seeking understanding

Saint Anselm of Canterbury was born in Aosta in northwestern Italy in the year 1033. Saint Anselm’s parents died when he was a relatively young age. At age fifteen he tried to enter the monastic life but faced opposition from his father. He lost interest in religion for a period of time in his life. Until in his twenties, when he entered the Abbey of Bec in Normandy, France. Three years after entering the monastic life, he was appointed prior of the monastery. And fifteen years later he was unanimously elected Abbot.

Saint Anselm would become one of the Church’s greatest thinkers and philosophers. He is known as the “father of scholasticism.” He is also said to be the most prolific and gifted writer between Saint Augustine (d. 430) and Saint Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274). He is known for his writings including but not limited to, Cur Deus Homo (“Why God Became Man”), Monologium, rationalizing the proof for the existence of God. His Proslogium, discussing the idea that God exists according to the human notion of a perfect being in whom nothing is lacking.

Saint Anselm is most famous for his development of the Ontological Argument for the existence of God.

This is what Saint Anselm teaches us.

That, than which nothing greater can be conceived, exists in the understanding alone, the very being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, is one, than which a greater can be conceived. But obviously this is impossible. Hence, there is no doubt that there exists a being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, and it exists both in the understanding and in reality.

Got that? You don’t? Isn’t it clear as mud? The gifted Catholic apologist, Jimmy Akin says it this way.

Instead of being too good to be true, God turns out to be too good not to be true.

Jimmy Akin

What does this mean? Saint Anselm says God is the kind of being who must exist; therefore he does exist. Other thinkers have argued the existence of God first by what we can see and observe in the world. When we observe the stars, sun, moon, laws of morality and nature, and other great wonders of creation, science can take us so far. So, God answers the rest. But the ontological argument starts with the very idea of God and says this idea shows God must actually exist.

Saint Anselm’s contributions to the Church extended outside the monastery and study. In 1093 Saint Anselm was made Archbishop of Canterbury by popular acclaim except his own. There is a painting depicting Saint Anselm being dragged to the throne of Archbishop by the English bishops. He was preceded as Archbishop by the great Lanfranc. Lanfranc was another exemplary figure from this period in the history of the Church. He was a gifted lawyer who renounced his life to become a monk at the Abbey of Bec. He was a contemporary of Saint Anselm in the monastic life.

Saint Anselm found himself in various ecclesial and political quandaries. He justly resisted King William II and Henry I and was exiled in France for the first time from 1097 to 1100 and again from 1105 to 1107. When Saint Anselm entered his first period of exile he asked to be relieved of his office as Archbishop, but the Holy Father refused. During the first exile Pope Urban II called Saint Anselm to Rome to prepare writings clearing defining the doctrine of the Holy Spirit.

After his second exile, Saint Anselm spent the remaining years of his life serving as Archbishop of Canterbury. There’s much history we haven’t offered here to be discovered about this period of exile. There was much back and forth between, the Pope, Saint Anselm, and the kings of England. The controversy was settled with the Concordat of London in 1107.

Saint Anselm died on Holy Wednesday April 21, 1109. His remains were laid to rest at Canterbury Cathedral near Lanfranc in Saint Thomas’s Chapel. Saint Anselm was canonized a saint by Pope Alexander III in 1163 and declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Clement XI in 1720.